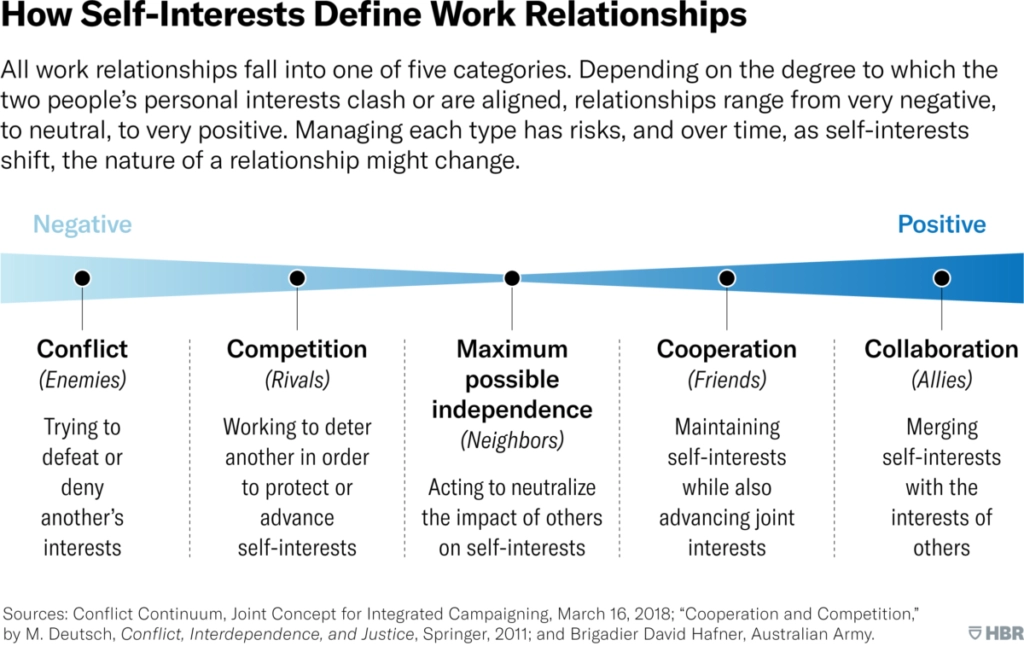

Relationships are negative when interests are opposed and the parties are either in competition or in outright conflict over goals. Bosses sometimes put us into these challenging situations to test whether we can rise above our personal feelings (or rivalries between teams or business units) to do what’s right for the organization. But most of us approach them warily, tending to focus on the harm that our counterparts have done in the past or could inflict in the future.

Work relationships are positive when people share interests and decide to cooperate to achieve selective goals or to collaborate when their goals are fully merged.

This feels the best, but if you assume that your partner has a purely positive intent and is totally aligned with you, and you’re mistaken, you’ve put yourself at risk.

In between are relationships in which two people largely work independently. But as we shall discuss later, these can be hard to maintain and carry their own risks.

Once you’ve figured out the type of relationship you and your colleague have, you can use various tactics to manage it. That requires you to step back from the existing emotional and behavioral dynamics and carefully analyze your situation.

Consider how your disparate and mutual interests align with the goals of your organization. Ask yourself what is in it for you and what is in it for the other person. How do his or her interests create risk for you? What can you tolerate, and what must you prevent? And how can you ensure that the benefits of working together are realized?

Relationships are negative when interests are opposed and the parties are either in competition or in outright conflict over goals. Bosses sometimes put us into these challenging situations to test whether we can rise above our personal feelings (or rivalries between teams or business units) to do what’s right for the organization. But most of us approach them warily, tending to focus on the harm that our counterparts have done in the past or could inflict in the future.

Work relationships are positive when people share interests and decide to cooperate to achieve selective goals or to collaborate when their goals are fully merged.

This feels the best, but if you assume that your partner has a purely positive intent and is totally aligned with you, and you’re mistaken, you’ve put yourself at risk.

In between are relationships in which two people largely work independently. But as we shall discuss later, these can be hard to maintain and carry their own risks.

Once you’ve figured out the type of relationship you and your colleague have, you can use various tactics to manage it. That requires you to step back from the existing emotional and behavioral dynamics and carefully analyze your situation.

Consider how your disparate and mutual interests align with the goals of your organization. Ask yourself what is in it for you and what is in it for the other person. How do his or her interests create risk for you? What can you tolerate, and what must you prevent? And how can you ensure that the benefits of working together are realized?

Conflict

In an outright conflict your counterpart is trying to take something that you want or need. It is a zero-sum relationship that ends when one party wins and the other loses the sought-after reward, such as a promotion or a plum assignment. Consider Jim and Jane, who are both being considered for a senior managing director position at a large private wealth-management firm. (All the case studies in this article are hypothetical but are drawn from various real scenarios we have studied.) Jane has worked for months to cultivate a prospective client, and if she succeeds, it could be a deciding factor in whether she gets promoted. She learns from a junior associate that Jim is also trying to land this high-net-worth individual, even though he knows that Jane is already in pursuit. He’s done this before, which is why she has grown to loathe him. If Jane ignores the situation, Jim will no doubt press on. If he wins the account, he’s unlikely to share any of the credit. Her peers and subordinates might then lose respect for her for not taking steps to protect herself, given that Jim’s predatory behavior is widely known. But if she directly confronts Jim, it could force others to take sides, and she might find herself abandoned by colleagues who fear retaliation from Jim, want to be on the winning side, think that she’s the one being petty, or have concern only for the firm’s bottom line. To manage the situation, Jane will need to figure out the best way to fight back without burning bridges. That requires emotional maturity and discipline. She can start by considering her counterpart’s strengths. (You need to know your enemy well and even acknowledge why he might be hard to beat.) What might the client value in Jim that Jane doesn’t have, and what could she do to change this? She also needs to revisit the importance of the issue in contention. Is the deal really vital to her promotion? Next she should consider workarounds or countermoves. Perhaps she could let Jim take this win and project her worth to senior leadership in other ways. Or if she determines that landing this client is key to her advancement, she could reach out to some of Jim’s prospects and use that as leverage in a discussion about how she and Jim could create and abide by boundaries. In a conflict relationship you need to be clear about what you must protect and what’s not possible, given the circumstances. Confrontation is both necessary and costly, so work closely with allies and do not engage your rival alone.Competition

This type of rivalry is very common in workplaces where pay and opportunities are routinely allocated by assessing and comparing the performance of employees. You and your colleague want the same things, but supply is limited. Unlike an outright win-or-lose conflict, competitive situations offer some flexibility, because value can still be found in other, albeit less attractive, options. Consider Michael and Ellen, who’ve been asked by their boss to colead a priority project: developing their company’s new diversity, equity, and inclusion plan. Success or failure on the assignment will have an impact on the career trajectories of both of them. Michael would like to work cooperatively with Ellen but is deeply skeptical that he’ll be able to do so, since she has a reputation for throwing colleagues under the bus in difficult situations. While he’s confident that they can produce good ideas together, he worries that when they present their recommendations to their superiors, Ellen will insinuate that the best-received ones are hers and the more-controversial ones his. Michael has several risks to consider when formulating a strategy for dealing with Ellen. If he raises his concerns at the outset, she’s likely to view it as an attack or dismiss him as paranoid, since she hasn’t done anything wrong yet.

If he simply works with her in good faith, he may face the lopsided outcome he fears: her taking all the credit for good work and blaming him for any stumbles.

However If he takes a page out of her previous playbook and tries to secretly compete with her, using less-than-honest tactics—withholding key information, for example—he might develop a reputation just as bad as hers.

The right move in cases like this one is to recognize where your goals and your rival’s are compatible and where they’re not and work from there to improve the odds of good outcomes while minimizing unwanted ones.

For example, neither Michael nor Ellen wants this project to fail, and both are committed to enhancing DEI at their company. In every conversation with her, he will want to emphasize those shared goals and the importance of achieving them as a team.

Perhaps he can rein in her competitive behavior by eliminating scenarios in which she might be tempted to undermine him.

One option would be to get her to agree to create an ad hoc review committee with members from multiple departments to provide feedback and endorse the final recommendations.

Or maybe he could persuade her that their bosses—instead of them—should present the results.

By recognizing what drives a rivalry, those in it can find a way to reduce competition.

Michael has several risks to consider when formulating a strategy for dealing with Ellen. If he raises his concerns at the outset, she’s likely to view it as an attack or dismiss him as paranoid, since she hasn’t done anything wrong yet.

If he simply works with her in good faith, he may face the lopsided outcome he fears: her taking all the credit for good work and blaming him for any stumbles.

However If he takes a page out of her previous playbook and tries to secretly compete with her, using less-than-honest tactics—withholding key information, for example—he might develop a reputation just as bad as hers.

The right move in cases like this one is to recognize where your goals and your rival’s are compatible and where they’re not and work from there to improve the odds of good outcomes while minimizing unwanted ones.

For example, neither Michael nor Ellen wants this project to fail, and both are committed to enhancing DEI at their company. In every conversation with her, he will want to emphasize those shared goals and the importance of achieving them as a team.

Perhaps he can rein in her competitive behavior by eliminating scenarios in which she might be tempted to undermine him.

One option would be to get her to agree to create an ad hoc review committee with members from multiple departments to provide feedback and endorse the final recommendations.

Or maybe he could persuade her that their bosses—instead of them—should present the results.

By recognizing what drives a rivalry, those in it can find a way to reduce competition.

Independence

In the middle of the spectrum is independence, which entails deliberately reducing your reliance on others as much as possible—evading the problem rather than trying to fix it. Consider Scott, who felt that his colleague Nigel often bullied him. To avoid having to deal with Nigel, Scott got his boss to restructure their respective responsibilities so that they would interact less frequently—just in formal meetings when the rest of the team was present. One challenge with this approach is that it is difficult to maintain over the long term. Scott should consider how he will behave if circumstances change and he suddenly has to reengage with Nigel. Another is that avoiding Nigel might also isolate Scott from potential allies who could help him perform his job better—teammates who think he’s being non-collegial and is putting his own interests above the group’s. Given those dangers, we don’t highly recommend this approach. Instead, people in Scott’s situation should consider treating the relationship as a conflict or a competition.Cooperation

In a cooperative relationship you and your counterpart share key interests but also have separate ones, so you choose to work together on specific issues where your interests do align and not to compete where they don’t. That doesn’t require you to like or make any material or long-term investments in each other. It’s just a mutually beneficial transaction in which each party brings something to the table. Take Mohammed and Roberto, peers tasked with an assignment beyond their normal responsibilities: pooling their expertise on BRIC countries to produce an economic forecast for their organization, which sells research and analysis to corporate clients. Both will benefit if the report attracts media attention, draws new subscribers to their company’s regular annual forecast, and builds the firm’s credibility and standing.Collaboration

Collaboration happens when two parties have many key mutual interests and would both benefit from investing in the relationship to help each other. This is the situation that Sara and Maryam found themselves in when their respective employers assigned them to colead a small pilot venture that paired the coach-client matching technology of Sara’s firm with the deep coaching experience and client list of Maryam’s company. The assignment entailed creating new shared processes for managing coaches, soliciting clients, and ensuring there would be joint accountability if something went wrong. This work promised to be hard but enjoyable; they’d both learn new things and build a venture that neither firm could have created alone. While such relationships feel psychologically safe and promise the most mutual gain, they are the hardest to disengage from if interests change, because the parties’ resources are intermingled. So at the outset Sara and Maryam should be cautious and take the time to understand their respective commitments—and those of their organizations—to the endeavor. That should include developing detailed plans for different scenarios, outlining their implications for each coleader and how they will be handled. For example, what happens if one company wants to pull back and the other wants to move forward, becomes the dominant backer, and insists that its person run the venture? Would the other party be willing to stick it out in a secondary role? Or if one company takes over the project and wants Sara and Maryam to continue to colead, would they both be willing?

. . .

We all navigate a range of cooperative rivalries at work. Understanding and figuring out how to optimize each of them is crucial. The solution is not to find positive relationships and avoid negative ones. You must recognize that conflict and competition inevitably arise among interdependent coworkers but can still be managed in ways that reap rewards; that while independence might seem like a solution it is rarely, if ever, a panacea; and that your goals and your work partners’ will evolve over time. Career success depends on relationship management as much as any other skill. Get it right, and both you and your organization will benefit.Source: https://hbr.org/2022/03/when-to-cooperate-with-colleagues-and-when-to-compete?registration=success